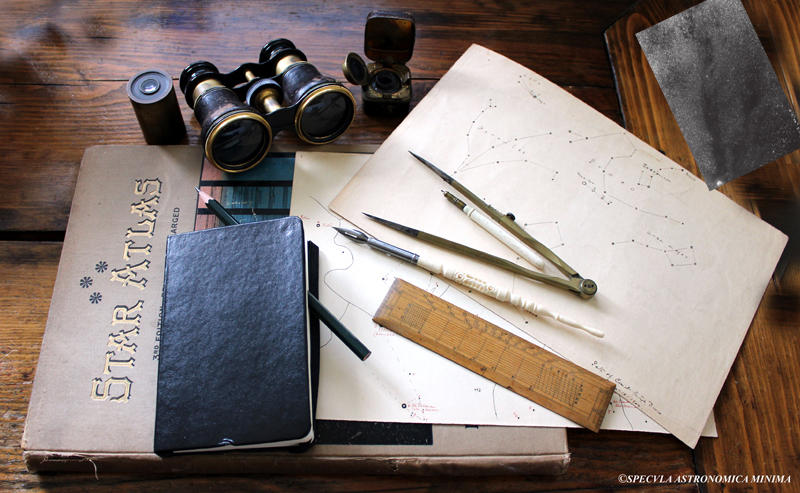

There's something all but magical about scientific notebooks, with their promise of bringing the viewer into the space where science happened in the moment—almost as if in turning the pages one can peel back intervening time to stand with the observer as the scientific record is made. Our imaginations at play with the materiality of the artifacts, our several understandings of how science may have been done, and who did the science, help conjure the spell of such relics. Even when scientific notebooks are opened for data mining, historical or scientific, that aura is never entirely dissipated. This is as true for astronomical logbooks as for any first or second generation record of observations made "in the field"—made in any field.

The serious study of scientific notebooks in all their variety and variety of aspect is a relatively recent scholarly activity. Collective studies of various cases and themes have appeared, such as Reworking the Bench: Research Notebooks in the History of Science, ed. Frederic L. Holmes, Jürgen Renn, and Hans-Jörg Rheinberger, Archimedes 7 (Dordrecht–Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003), along with monographs on certain periods or types of notebooks, such as Richard Yeo, Notebooks, English Virtuosi, and Early Modern Science (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press, 2014).

We are presently in what seems a golden age for the unfolding of the potential of electronic hosting, searching, and analysis of corpora of texts. We can all benefit from these developments, particularly in the toppling of barriers to the ready consultability of electronic facsimiles of scientific notebooks. Now one can call up a "laboratory" notebook of Sir Isaac Newton's, Cambridge University Library, MS Add.3975, to look at his alchemical and other researches, as easily as one can consult the chemical notebooks of Sir John Herschel in the Science Museum in London, MSS/0478/1-4. Or, if there is a question about the observations of the Rev'd Nevil Maskelyne taken during his 1761 transit of Venus expedition, his Journal of a Voyage to St. Helena, Cambridge, RGO 4/150, is not remote in terms of cyberspace.

In regard to some of the matter mentioned in the podcast, Simon Newcomb's scientific account of how he set the record straight about Fr. Hell's 18th-century transit of Venus observations, through recourse to Fr. Hell's observational logbooks, can be found in Simon Newcomb, "On Hell's alleged falsification of his observations of the transit of Venus in 1769", in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 43, 7 (1883, May), 371-381. He also wrote a more popular account in his autobiography: Simon Newcomb, The Reminiscences of an Astronomer (Boston and New York: Houghton, Mifflin and Company), pp. 156-160.

A few pages from James Keeler's LIck Observatiory logbooks are avaiable for consultation (Jupiter, & some spectra; unfortunately, the full notebooks have not been made publicly accessible. Perhaps one day more of the invaluable logbook treasuries of the Lick Observatory, and the Observatoire de Paris will come online).

For a modern reevaluation of Alexander Marshack's attempt to interpret markings on Upper Paleolithic and later artifcats as "astronomical" records, see the studies in: An Enquiring Mind: Studies in Honor of Alexander Marshack, ed. Paul G. Bahn, American School of Prehistoric Research Monograph (Oxford–Oakville, Conn: Oxbow Books, 2009).

A few of the few surviving observational records from the RASC's earliest year are images of Venus, and Jupiter by Andrew Elvins (note: these may very well be second generation images). Little else in the way of graphic observational record survives from our earliest period. Another of the rare survivals was illustrated in the supplement to podcast 1, namely the use of the verso of the draft of our surviving first bylaws for observational notes on the solar eclipse of 1869 August 7.1

William F. Denning, Telescopic Work for Starlight Evenings (London: Taylor and Francis, 1891), is certainly still worth reading. On Denning, see Martin Beech's useful short biographical note.

Mary Byrd's guidelines for an astronomical notebook are in: Mary E. Byrd, A Laboratory Manual in Astronomy (Boston: Ginn & Company, 1899).

And, very much of the present, David Levy's logbooks can all be consulted online. For background, see: Roy Bishop, "David Levy and his Observing Logs", and R.A. Rosenfeld, "David Levy’s Logbooks in Context".

Guidelines for present amateur practice are offerred in current editions of the RASC Observer's Handbook, and (briefly) in Sky & Telescope.

—R.A. Rosenfeld

A transcript of this podcast is available.

Footnote

1. This reminds us of how parsimonious our Victorian ancestors could be with paper. Even some of those who were well-off regulated their use of paper in an almost Scrooge-like fashion. A telling example from the period of the Society's revival in the 1890s survives in Sir Adam Wilson's employmeny of the verso of a legal document for his observational drawing of the transit of Mercury of 1891 May 9.

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 179.28 KB |