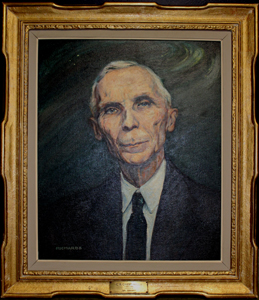

C.A. Chant's (1865-1956) prominent place in the historical narrative of Canadian astronomy is assured. In the course of a nearly seventy-year career, seemingly comfortably contained by inherited bounds of training, society, and ability, Chant was able to establish the first lasting department of astronomy and astrophysics in a Canadian university, the first Canadian undergraduate degree in the discipline, the first major astrophysical installation within a Canadian university, and what in time became the leading English language observationally-oriented ephemeris in handbook form. Additionally, he re-established the sole Canadian astronomy journal of record, and with colleagues extended the organization of the RASC to some degree. All of these entities continue in some form or other to this day. It is a notable legacy, stemming from a life of steady application.

The public image of Chant doesn't seem to have changed, or developed in six decades. It is the image which can be found in the obituaries published upon his death; John F. Heard, "Clarence Augustus Chant", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 117 (1957), 250-251, John F. Heard, "Clarence Augustus Chant", JRASC 51, 1 (1957 February), 1-4; Helen S. Hogg, "C. A. Chant, Father of Canadian Astronomy", Science 125, 3247 (1957 Mar. 22), 357-358 (this obituary, mentioned in the podcast, unfortunately lurks behind a paywall). Few alive today would have known Chant; for most of us, his public image is the product of published accounts.

The public image of Chant doesn't seem to have changed, or developed in six decades. It is the image which can be found in the obituaries published upon his death; John F. Heard, "Clarence Augustus Chant", Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 117 (1957), 250-251, John F. Heard, "Clarence Augustus Chant", JRASC 51, 1 (1957 February), 1-4; Helen S. Hogg, "C. A. Chant, Father of Canadian Astronomy", Science 125, 3247 (1957 Mar. 22), 357-358 (this obituary, mentioned in the podcast, unfortunately lurks behind a paywall). Few alive today would have known Chant; for most of us, his public image is the product of published accounts.

The most balanced "recent" assessment of him occurs in the course of Richard A. Jarrell's The Cold Light of Dawn: a History of Canadian Astronomy (Toronto–Buffalo–London: University of Toronto Press, 1988), pp. 126-133, but it is necessarily brief, and it appears to have been absorbed less effectively than it merits. The result? The community which is familiar with the name Chant has been content to live for six decades with an unchanging public image of him, which implies complacent disinterest in the man. In those six decades no one has undertaken to write a substantial biographical memoir of "the Father of Canadian astronomy", and no properly researched account of any aspect of his career has been published, to say nothing of a full-length biography. Fortunately, the doctorial work currently being undertaken by Andrew Oakes at the Institute for the Philosophy and History of Science and Technology (IPHST) at the University of Toronto, should eventually result in the issue of the first full-scale study of Chant.

One particularly valuable literary source for Chant's life is his autobiography, which runs to about 850 pages of typescript (it is not accessible in electronic format over the internet, but it can be consulted at the University of Toronto Archives & Records Management Service, retrieval code UTARMS A1974-0027-010). His intention was to have it published by the University of Toronto Press. The Press opted to issue only an eighth of the work, namely the story of the establishment of the David Dunlap Observatory, under the title Astronomy in the University of Toronto: the David Dunlap Observatory (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1954)—which is now a very rare book! The real reason for the Press' reluctance to issue the autobiography in its entirety is hinted at by Jack Heard; the style and nature of the narrative would not meet with much public interest. Several historians of Canadian astronomy have privately concurred.1 It is, none the less, a work of value for what it reveals about how Chant saw his role in things, and how he chose to shape what was to be the public narrative of his life. As with any autobiographical account, it is best read both sympathetically, and with due caution. Some of his correspondence also survives (UTARMS A1974-0027/001–A1974-0027/005).

One major theme of the podcast is the difficulty in achieving a meaningful evaluation of a scientific communicator who was known as a lecturer, when neither the lecturer nor any recordings of the lecturer are extant. To communicate science live, even in a soberly restrained way, requires the communicator to be in motion. Much of the effectiveness of live science communication comes from its non-static, performative nature.2 We go to hear scientists talk about their research because we want to hear about it from them, in real time, and in the same physical space. As was said in the podcast: "the choice of words, the style of delivery, the quality of the speaker's voice, the degree and kinds of interaction with the audience, the decor and sound of the auditorium, the visual appeal of the slides or other apparatus, the drama and display of a publicly staged experiment, the lecturer's sense of timing, and the coordination of the various elements", combine to create the experience of live science communication. To those elements we can also add the composition, disposition, and mood of the audience. Without those constituent parts, and particularly without the speaker speaking, we can at best only experience an insubstantial shadow of the live presentation. If all we have left are vestiges of a lecture—a written text, a woodcut or still photograph, or a piece of apparatus—we haven't really got enough to bring us into the very time and place when and where the lecture was in course.

We know from reports (1, 2, & 3) that Chant had a reputation as a speaker, and that he could effectively manipulate the apparatus of the physical lecturer. In the podcast, we ask: "How then, can we recapture what he [Chant] was really like as a live communicator of astronomy? Is there, in fact, some way this could be imaginatively done? Even with one of his texts in the hand of a good and intelligent actor, speaking in a surviving space Chant could have used, would the experience be of more than antiquarian value?". We elected not to provide an answer in the podcast, but we have no hesitation in stating that it would be of more than antiquarian interest. An actor performing one of Chant's lectures using a surviving text, and delivering it in the style of Chant's day (period vocal delivery is much more important than relying on period costume in the hope that it might create a vintage "mood"), in a hall that he used or its equivalent, and employing surviving contemporary apparatus, could provide a modern audience with:

- a live reconstruction of what such an event would sound, and look like;

- a basis on which to compare a science lecture of Chant's day with scientific lectures of the second decade of the 21st century;

- the revelation of useful communication techniques or strategies that have fallen by the wayside, but which could be effectively adapted for present use;

- some insight into how the texts we read from a century ago were actually experienced by audiences then, which we might bear in mind when reading texts meant for oral delivery from the period.

Such an experiment wouldn't of course bring us into the lecture-hall presence of a miraculously revived Chant, accurate down to every last detail of sound and sight, but it would provide us with an experience of what his lecturing may have been like. The experience could be as instructive as restaging past experiments has proven to be in understanding past science—and a potential route to discovery itself about how knowledge was (and is) transferred.3

Documents regarding Chant's participation in the Lick Observatory's 1922 solar eclipse expedition are most ably set in the wider context of the Einstein tests for the period in Jeffrey Crelinsten, Einstein's Jury: The Race to Test Relativity (Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2006), pp. 201, 229. These reveal Chant's inexperience in conducting critical astronomical observations, and his lack of a reputation among leading research astronomers. The formal report of the Canadian section of the Lick expedition was published quite expeditiously (C.A. Chant and R.K. Young, Pubs. DAO, 2, 15 [1923], 275–85). As it turned out, Chant wasn't the one to perform the exacting work of measuring the plates. That was left to R.K. Young to carry through.4

Chant's only book on astronomy, Our Wonderful Universe (1st 1928; rev. ed. 1940), was in the tradition of popular astronomical expositions, by then well-established. It did quite well for Chant, and was the chief vehicle through which his name spread throughout the world as an astronomy popularizer, although the extent to which that happened has not been critically examined, like so much else about his career. The first edition can be viewed online. Uniquely, for a Canadian book of astronomical popularization, it was translated into five foreign languages; German as Die Wunder des Weltalls; eine leichte Einführung in das Studuim der Himmelserscheinungen (1929), Czech as Divy Vesmíru, úvod ve studium nebeských zjevů (1929), Polish as Cuda wszechświata, łatwy wstep do poznawania nieba (1931), Spanish as Nuestro maravilloso universo; introducción sencilla al estudio del cielo (1946), and French as Notre univers merveilleux, initation à l'étude du ciel (1952) . The recent reprint (unrevised!) by a smaller U.K. press, is both attractive, and reasonably priced.

There are no recent assessments of how influential in Ontario schools and beyond Chant's commercially available set of One Hundred Astronomical Lantern Slides (1930) & Handbook proved to be. The sets now seem to be very rare, and the RASC is fortunate to have one with the accompanying Handbook. The Handbook can be read here.

The story of the Brashear reflector is partly told in R.A. Rosenfeld, "The Affair of the Sir Adam Wilson Telescope, Societal Negligence, and the Damning Miller Report", JRASC 105, 5 (2011, October), 210-213. After the podcast was recorded some new documents came to light which indicate that the instrument was indeed returned to the Society, and that while Chant may have been responsible in part for its loan, he was not responsible for its eventual disappearance. The boundaries between the RASC and the University of Toronto Astronomy and Astrophysics Department from the founding of the latter till as late as the early 2000s were at times very permeable, and it seemed books and apparatus belonging to the former could one way or the other end up on long term "loan"—formally, or informally—to the latter. Chant was in a leadership position in both organizations when this practice was at its height. There were doubtless compelling reasons at the time for such pratices, but the frequent casualness in record keeping has caused subsequent difficulties in tracing instruments, and determining provenances.

—R.A. Rosenfeld

A transcript of this podcast is available.

Footnotes

- One is reminded of the tale told by Trajano Boccalini (1556–1613) of the man who for sins against brevity is punished by being forced to read the "war on Pisa" from Francesco Guicciardini's (1483-1540) History of Italy. After enduring the supreme tediousness of a single page, he begs to be sent to the galleys, then to be immured between two walls, and then flayed alive in preference to being forced to read any more from the work of supremely epic dullness. ↵

- We sensibly use "performative" according to the first definition given in the Oxford English Dictionary (2000) "Of or relating to performance", and not according to the poorly coined and artificially constrained meaning derived by gender theorists and some philosophers of language from J.L. Austin's 1950s usage. That language is a prime tool in the construction of gender ought to be obvious, but so is the nomenclatural poverty of using "performative" to denote "designating or relating to an utterance that effects an action by being spoken or by means of which the speaker performs a particular act". The broader use of "performative" in a way which could equally apply to a concert performer, and actor, or a physics lecturer, as for example in SungWon Hwang & Wolff-Michael Roth, "The (Embodied) Performance of Physics Concepts in Lectures", Research in Science Education 41 (2011), 461-477, is more flexible, useful, and intuitive ↵

- On remounting past experiments, see the excellent presentation in Hasok Chang, "2015 Wilkins-Bernal-Medawar Lecture: Who Cares About the History of Science?", Notes and Records of the Royal Society 71 (2017), 91-107, and the online version. ↵

- Chant's most significant piece of original research occurred when he gathered and published the eyewitness reports to the Great Meteor Procession of 1913 February 9, and attempted an analysis of them, R.A. Rosenfeld & Clark Muir, "Gustav Hahn's Graphic Record of the Great Meteor Procession of 1913 February 9", JRASC 105, 4 (2011 August), 167-175. ↵

|

Chant portrait (above): The portrait bears the following inscription on the back of the canvas, "Dr. Chant"/ by Phyllis H. Richards, A.O.C.A./ 1960/Presented to the R.A.S.C./by/Carl Reinhardt. It also bears a photocopied page taped to the back, with details of the portraits' presentation drawn from the minutes of the RASC National Council for 1960 October 3 (p.1):

The Society's office mentioned in the text was located at that time at 252 College Street, Toronto.

Carl Reinhardt was among our more colourful members.

Regarding Peter M. Millman's address, Chant was neither a "Charter member", not strictly speaking a "founder", for he did not join the Society till the end of 1892; the Society's founding can be taken as either 1868, or 1884 (its revival), and its letters of incorporation date from 1890.

|

| Attachment | Size |

|---|---|

| 209.24 KB |